Many of us challenging mainstream health advice find ourselves continually questioning whether the unending stream of inaccurate information from newspapers, academics, and experts is intentional or just ill-advised. The latter explanation would be a far more comforting idea, as it would imply a non-malevolent world where I’m guessing we’d all prefer to live. Yet, having spent two decades investigating diet and health, I’ve concluded that while there are many well-meaning experts out there, the forces suppressing good science and intentionally promoting misinformation—technically known as “disinformation”—are driving the narrative. Below are some examples.

I’ll focus on the low-carbohydrate diet, because it’s been shown to be so effective in reversing many chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, a cruel and costly affliction affecting an estimated 462 million people worldwide. Low-carb can be life-saving for these people. If it were a pill or a device backed by pharmaceutical interests, we’d have been reading about it daily, much as we do now with weight loss drugs like Wegovy. Instead, our top experts and the media have remained largely silent on low-carb.

There’s no question that these diets, because they reverse diseases, constitute a major threat to the pharmaceutical industry, which makes its money from people being sick. Chronic diseases that require lifelong medications are a particular sweet spot of revenue for this industry. Pharmaceutical companies spent north of $8 billion on media advertising last year (up from $6 billion in 2020), and their goal, cynical as it sounds, is to maximize their sales, not make us healthy enough to quit their products.

Low-carb diets, because they reverse disease, are also a threat to Big Food, whose ultra-processed foods are mostly derived from the very sugars and starches that low-carb diets avoid. I’ve written about how Unilever, Danone, Nestlé, the Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo. and other processed food companies were found to dominate global food policy. Nestlé, Danone, General Mills, and Kellogg’s were also among the companies found to have direct ties with the expert group behind our current U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The entity with the most ties to these guidelines’ experts was the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI), a multinational food industry lobbying group that was started by an ex-Coke vice president and whose members include many of the same familiar names: Unilever, Coke, PepsiCo, Kellogg’s, and General Mills.

How did that turn out for our food policies? As far as I know, low-carbohydrate diets have never been discussed at the global level (The “EAT-Lancet” diet, the forerunner for adoption by the United Nations, contains 50-55% of calories as carbohydrate, or roughly twice that of a low-carb diet).

As for the U.S. guidelines, I found that the lead agency on this policy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, suppressed information on these diets and in 2020, claimed that no trials on them had ever been conducted—when already hundreds had been published, including one by a member of the guidelines’ expert group itself.

While authorities seem intent on ignoring the diet’s very existence, we see in parallel a continual drumbeat of headlines warning us of its ill effects, and not just minor ones. If you do a Google search for low-carbohydrate and “premature death,” or “all-cause mortality,” or “mortality,” you’ll turn up endless pages of headlines. Some of them are truly terrifying, such as “Low Carb Diets Have Been Linked to an Early Death: Keto lovers, beware” (Men’s Health), “Cutting carbs could lead to premature death” (Washington Post), and “A Low-Carb Diet Could Cut 4 Years Off Your Life, So Just Eat the Damn Pasta” (Esquire). Many others warn of heart disease: “Keto diet is not healthy and may harm the heart (Harvard Health), and “'Keto-like' diet linked to higher risk of heart disease” (ABC News).

How can we explain this proliferation of anti-low-carb headlines while not a single U.S. news agency will report on the diet’s benefits for diabetes? Industry involvement in both nutrition science and the media is pervasive and undeniable. Also undeniable is that most of the studies generating these headlines are based on the flimsiest of evidence—or simply no evidence at all. If the aim is to use weak science to garner scary news headlines that scare people off keto, then mission accomplished. As the master propagandist Joseph Goebbels taught us, a lie repeated often enough becomes the truth.

The first example comes this week from Australia, where headlines, including one on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald, trumpeted that low-carbohydrate eating causes diabetes. Just on its face, the idea that a diet could cause a disorder it has been shown, in multiple clinical trials, to reverse is absurd. If the peer reviewers for the journal had been doing their job, the paper covered by these news reports would never have been published.

To review the study briefly: researchers from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Monash Universities, both in Australia, analyzed data collected 16 years ago on 41,513 Melbourne residents. The subjects who self-reported having diabetes also had significantly lower physical activity, higher rates of smoking, a lower socio-economic status, higher BMI (body mass index), higher abdominal obesity, higher likelihood of a family history of diabetes, and a lower “healthy eating” score (reflecting an overall poor diet). So, these folks were not healthy in many ways. Researchers try to “adjust” for all these factors, but they can’t, effectively (For instance, imagine trying to adjust accurately for the impact of the “healthy eating” index, which itself has nine components.)

In the end, the authors found only a 3% difference in the risk for diabetes between low- and high-carb eaters. This is a minuscule, meaningless difference. And don’t forget that this tiny number is contradicted by far more rigorous data from clinical trials showing that a very low-carb diet resolves the disease.

The kicker in this study was that the so-called low-carbohydrate group was not even low-carb. Although a single definition of “low-carbohydrate” is elusive, experts actively conducting trials on this diet have generally agreed to define it as one where carbohydrates are kept below 130 grams daily. That’s about 30% of calories for an average 2,000-calorie/day diet. Twenty-five percent (25%) was the definition used by the expert group reviewing the science of this diet for the 2020 Dietary Guidelines.

By contrast, the Australian team used 37.5%, a definition created by researchers at the Harvard T.S. Chan School of Public Health. Harvard is prestigious, true, yet Walter Willett, its leader of 25 years (1991-2017), was driven by a strong bias for a vegetarian diet with carbohydrate-rich foods such as whole grains, nuts and seeds (which the school continues to promote). Low-carb is very different—the competition, if you will-- and Harvard’s view of it has mostly been wary to critical. Also, the school itself conducts no clinical trials on the diet, so its researchers have no direct experience with how it works. These factors make Harvard a less-than-authoritative source for defining low-carb.

Even so, the same or similarly non-standard definitions have been used in many other observational studies, also generating frightening news reports. For a 2021 paper in Nutrients on which I was a co-author with 11 low-carb researchers, I examined all the papers that linked low-carb to increased mortality (dying early). In the nine papers I identified, “low-carbohydrate” was defined as follows (country of study follows in parentheses): 53% (Japan), 40% (Sweden), 40.9% (United Kingdom). 37%, 39%, 47.3%, 40%, 37.2%, and 43.2% (United States). So, not low-carb.

Some of these studies led to those headlines about how low-carb kills, and a reasonable readers would be scared off. They would have no idea that more rigorous clinical trial evidence had established low-carbohydrate diets as highly effective for treating not just diabetes but also hypertension, the vast majority of heart disease risk factors, and even, potentially, cancer. Since these chronic diseases are responsible for most deaths in America, how could a diet that ameliorates such conditions end up ushering in our early demise? It’s a paradox— and one that the authors of the papers listed above make little or no attempt to reconcile.

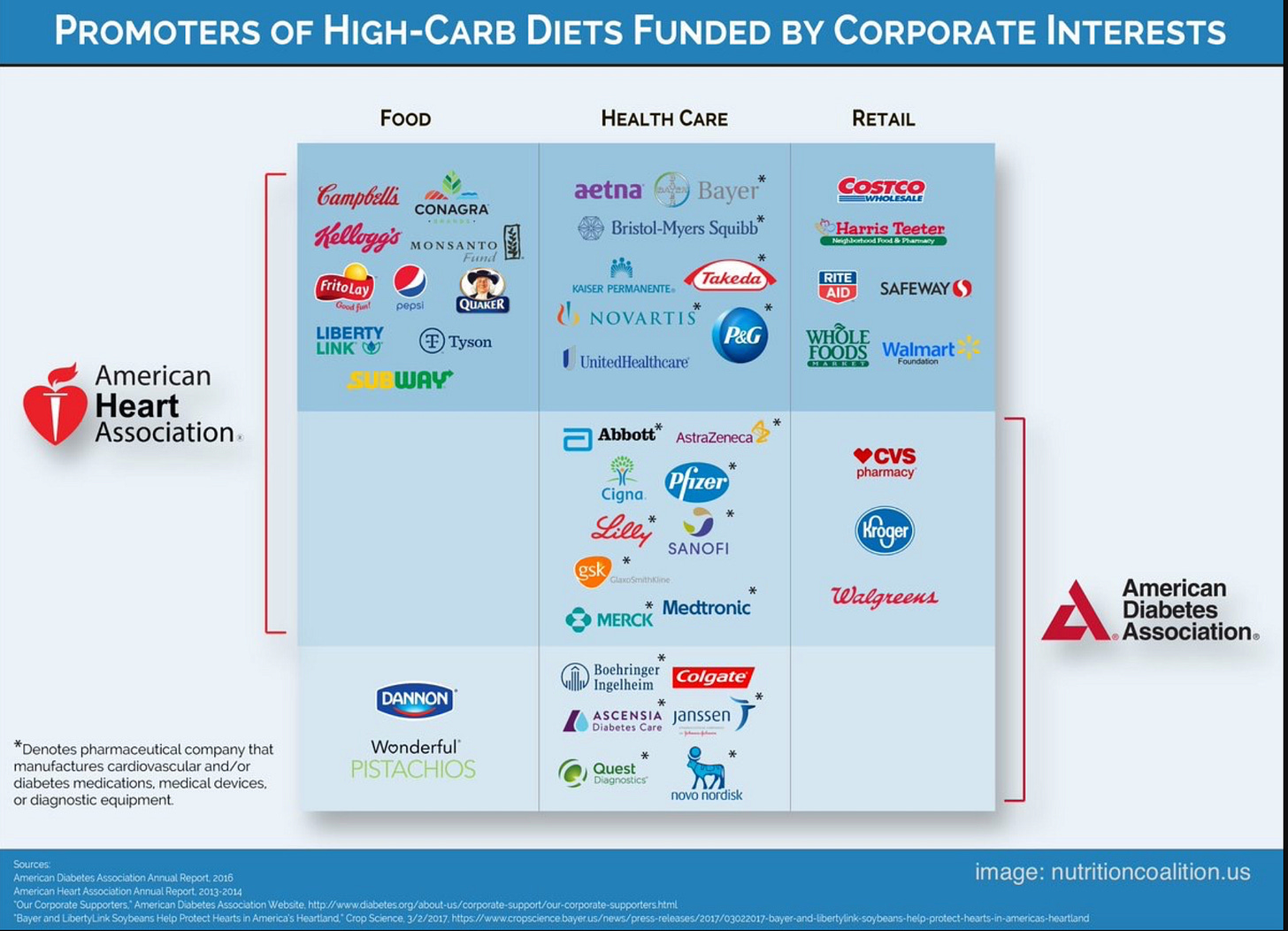

The following two examples of weak (or no) science being catapulted into worldwide headlines come from the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC). These groups reported receiving 20% (in 2014) and 38% (in 2012) of their funding from industry, respectively.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unsettled Science to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.